At 6-foot-6, John Henry Browne towers over everyone in his plush Pioneer-Square office. His neat suit hides the barbed-wire tattoo inked on his right forearm, and his short hair—which he used to wear in a footlong ponytail, to the annoyance of courtrooms —is slicked back neatly. It is mostly grey; he turns 70-years-old this week.

Browne has been a lawyer for nearly 50 of those years. And as he nears retirement, he wants to be remembered as more than the man who saved murderers.

If you haven't heard of Browne, the results of a quick Google search may be alarming. The words “murderer” and “serial killer” are practically synonymous with his name.

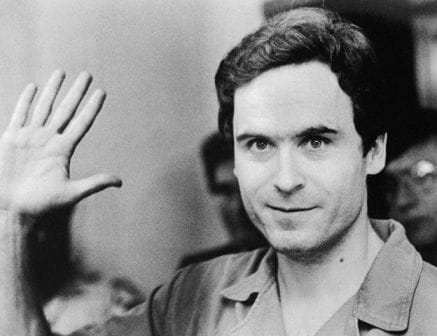

The Seattle-based attorney is notorious for his high-profile defense work. From Ted Bundy to the “Barefoot Bandit” to the murder of 16 Afghani civilians, Browne’s legal career has kept him in the spotlight since the 1970s, and he’s been fodder for the media ever since. Once labeled “a pit-bull on crack” by a prosecutor and told by a state justice that he needed a spanking, Browne boasts a reputation that fuses belligerence, charm, and a willingness to represent the worst.

In his recently published autobiography — which he discussed with Crosscut in a candid interview — Browne pens a very different version of himself. Aptly titled “The Devil’s Defender,” the book is full of colorful moments: a decision to become a lawyer after a weekend spent in jail, nearly slipping LSD into Vice President Spiro Agnew’s cocktail, and a rainy night in 1983 where he found himself face down a pile of cat feces after trying to score cocaine.

But at its heart is a question, one that likely haunts other lawyers who have defended undeniable killers in court: does fighting on behalf of evil make you evil too?

--

“I didn’t think people were born evil,” says Browne. “Until I met Bundy.”

At the time Browne met Ted Bundy, his most famous client, he was defending women who had murdered their abusive husbands. After suffering years of abuse, both Ivy Kelly and Claudia Thacker were convicted of murder for shooting and killing their spouses. Citing battered woman syndrome, Browne presented arguments of self-defense for both. Both juries acquitted. This is the legacy Browne would choose for himself — “If I was going to be known for any one thing, I would probably choose the battered women.”

The outcomes helped set a legal precedent for battered women across the country, and “finally got people to recognize that there’s such a thing as battered woman syndrome,” he says.

Browne says his work on behalf of women stems from a place of respect, and that the world would be better off run women. Nevertheless, Browne identifies himself as a “serial monogamist” and once admitted to The New York Times that his marriages “would round up toward double digits.”

This preferred legacy, as defender of abused women, ended when he took on Ted Bundy as a client. Before their first conversation, which continues to haunt him 40 years later, Bundy had just confessed to the murder of more than one hundred people. His most recent victim was a child.

Bundy admitted in that conversation that he had ‘chosen’ Browne as his lawyer deliberately. Why? According to Bundy, the two of them were “so much alike.”

“It really freaked me out,” he says. “There’s no way in the world obviously I would think I was alike to a mass murderer, sociopath, narcissistic, asshole—although I’m sure I do have some of those tendencies.”

“I was staying in some really cheap motel… there was a cracked mirror in the bathroom—and I remember looking in the mirror and smoking like three cigarettes at the same time and saying “What the f**k are you doing here? Why are you with this guy? This monster, who thinks you’re alike?”’

While Browne doesn’t want his autobiography to be seen as yet another book about Ted Bundy, he admits that writing it helped him “purge” some of his dark past; he is now able to speak more freely about the famous serial killer.

“He [Bundy] would’ve wanted to be a defense lawyer,” he says. “He wanted to live in the waterfront house—he knew all about it—he wanted to have a girlfriend who was a Ralph Lauren model, he wanted to have motorcycles and cars.”

--

Bundy's fantasy was Browne's reality in the eighties.

After Bundy, Browne defended Benjamin Ng, who helped to execute thirteen people in the West Coast’s bloodiest massacre. Saving Ng from the death penalty was seen as nearly impossible, and Browne’s success at the task bolstered his reputation as one of the most zealous lawyers in the game. He was famous, he was rich, and he was—

“F**king miserable.”

At the time, Browne was an addict, taking drugs and drinking heavily. “Basically” he says, “I just didn’t like myself. I know that now.”

A friend who saw through his public bravado took him to a retreat in Death Valley. Under the instruction of consciousness teacher Dr. Richard Moss, Browne scrubbed toilets, prayed in sweat lodges, and stood on cliff sides. He dared himself to jump but didn’t. His legendary ego finally broke, and in his new sobriety, he began to develop a deep spirituality that he carries with him today.

These spiritual beliefs have saved him from going insane, he says. He still attends retreats. Along with the teachings of a number of philosophers— he rattles off Yogananda, Thomas Merton, and Matthew Fox — Browne says the crux of his spirituality can be summed up in one word:

“Compassion,” he says. “There’s all kinds of shit going on today that could cause me to become crazy… But I get myself back to trying to deal with everything with some compassion.”

But is it Browne’s sense of compassion that has saved so many killers from execution? Perhaps, but there’s more to the story.

--

“You've read the story about my girlfriend being murdered?”

Browne speaks haltingly for the first time in our long interview. He’s referring to his former girlfriend Deborah Beeler, to whom his autobiography is dedicated. Debbie was murdered in California in the ‘70s when Browne was at law school in D.C. Her case went unsolved.

“It’s still difficult for me to talk about,” he admits. Her death made him a death penalty advocate for some time, until she appeared to him in a dream. “She came to me and said ‘don’t believe in things that I never believed in, that’s not an honor to me.’”

The dream shook Browne to his core; he decides to spend his life getting the death penalty off of the table.

Capital punishment cases are usually costly, but Browne takes on many for free. Most recently he clocked 2,500 hours of pro bono work to defend Staff Sergeant Robert Bales, who murdered 16 Afghan civilians in an event known as the “Kandahar massacre.” Browne saved Bales from capital punishment by arguing that the former sergeant suffered from PTSD.

Browne says his defense of Bales went beyond fighting the death penalty; it was a stance against the system. During the case, Browne spent 12 days in Afghanistan. His disdain for war, and both the physical and mental damage it can do to people, is tangible. He outlines Bales’ character: class president, captain of the football team, a caretaker for the disabled. “Sergeant Bales was a victim of our system. You know, we just destroyed him. I took on Bobby Bales’ case to save him from the firing squad.”

The system that “destroyed” Bales is one Browne is renowned for his ability to navigate, though he insists things are “much worse off” ” than when he first became an attorney.

“You know the world’s a mess,” he says “the criminal justice system is a mess.”

But where does that leave the defense attorney, the person who defends criminals in a “mess” of a system?

This is a question that Browne has struggled with his entire career. Does helping people who do bad things, in a bad system, make you bad person?

Browne likens defense of criminals to looking out of a dirty window. He poses the metaphor: “If you look at the world through a dirty window all the time, is that all you see? The dirt?”

This isn’t the case for him, he says. He doesn’t think of himself as evil for defending those who may be. But, he says, “there are times that I think participation in the system—which is an oppressive system—is evil.”

--

Browne at a protest in Washington D.C. against the Vietnam War.

The question of evil is a major theme in Browne’s life, as well as his autobiography.

He is incredibly humbled by the success of the book, which he originally titled “Music, Metaphysics, and Murderers.” Music, he says, is a huge part of his life. He played bass in a band that once opened for Jimi Hendrix. His favorite artist is Leonard Cohen but he openly gushes over Sting, describing him as a “goddess.”

While murderers play a central role in his life’s work, not all of Browne’s cases are so unpleasant. In 2012 he defended Colton Harris-Moore, a case for which he received all of $1.00. Harris-Moore — also known as the “Barefoot Bandit” — led police on a wild goose-chase across three different countries over two years. He stole everything from food to airplanes, and Browne had to consolidate over 80 criminal charges in order to defend Colton. In what he describes as the best plea deal of his career, he obtained Harris-Moore a five-year sentence.

Harris-Moore will be working in Browne’s office upon his release in 2017. His life story is being made into a movie by 20th Century Fox.

Browne says Hollywood is also considering a film about his life, a fact he seems blasé about. Once, when asked who he’d want to play him, he promptly answered Danny DeVito. This startled the Fox reporter who’d inquired.

As our interview winds down, Browne checks his watch; he has to leave for prison soon. For someone who has a date with a murderer, he appears cheerful, but perhaps that’s not surprising. An addict saved by spirituality, a rebel turned successful attorney, and a man who preaches “compassion” but is used to dealing with killers, calling Browne an enigma is an understatement.

While 250 pages may help to unpack him, his story and his contradictions will be puzzled over long after he’s left the courtroom.

Photo credits:

Title photo by Associated Press. Other photos of Browne courtesy of the subject. Photo of Colton Harris-Moore is self-portrait. Photo of Ted Bundy from court archives. Photo of Robert Bales by Maj. Brent Clemmer.